(thoughts collected from others, mainly software engineers)

Kate Heddleston

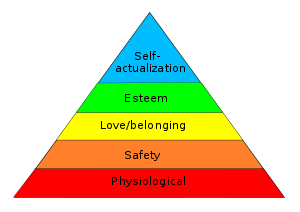

Since I started programming, discussions about ethics and responsibility have been rare and sporadic. Programmers have the ability to build software that can touch thousands, millions, and even potentially billions of lives. That power should come with a strong sense of ethical obligation to the users whose increasingly digital lives are affected by the software and communities that we build.

[…]

Programmers and software companies can build much faster than governments can legislate. Even when legislation does catch up, enforcing laws on the internet is difficult due to the sheer volume of interactions. In this world, programmers have a lot of power and relatively little oversight. Engineers are often allowed to be demigods of the systems they build and maintain, and programmers are the ones with the power to create and change the laws that dictate how users interact on their sites.

https://kateheddleston.com/blog/a-modern-day-take-on-the-ethics-of-being-a-programmer

2015

Ben Adida

Here’s one story that blew my mind a few months ago. Facebook (and I don’t mean to pick on Facebook, they just happen to have a lot of data) introduced a feature that shows you photos from your past you haven’t seen in a while. Except, that turned out to include a lot of photos of ex-boyfriends and ex-girlfriends, and people complained. But here’s the thing: Facebook photos often contain tags of people present in the photo. And you’ve told Facebook about your relationships over time (though it’s likely that, even if you didn’t, they can probably guess from your joint social network activity.) So what did Facebook do? They computed the graph of ex-relationships, and they ensured that you are no longer proactively shown photos of your exes. They did this in a matter of days. Think about that one again: in a matter of days, they figured out all the romantic relationships that ever occurred between their 600M+ users. The power of that knowledge is staggering, and if what I hear about Facebook is correct, that power is in just about every Facebook engineer’s hands.

[…]

There’s this continued and surprisingly widespread delusion that technology is somehow neutral, that moral decisions are for other people to make. But that’s just not true. Lessig taught me (and a generation of other technologists) that Code is Law, or as I prefer to think about it, that Code defines the Laws of Physics on the Internet. Laws of Physics are only free of moral value if they are truly natural. When they are artificial, they become deeply intertwined with morals, because the technologists choose which artificial worlds to create, which defaults to set, which way gravity pulls you. Too often, artificial gravity tends to pull users in the direction that makes the providing company the most money.

https://benlog.com/2011/06/12/with-great-power/

2011

Arvind Narayanan

We’re at a unique time in history in terms of technologists having so much direct power. There’s just something about the picture of an engineer in Silicon Valley pushing a feature live at the end of a week, and then heading out for some beer, while people halfway around the world wake up and start using the feature and trusting their lives to it. It gives you pause.

[…]

For the first time in history, the impact of technology is being felt worldwide and at Internet speed. The magic of automation and ‘scale’ dramatically magnifies effort and thus bestows great power upon developers, but it also comes with the burden of social responsibility. Technologists have always been able to rely on someone else to make the moral decisions. But not anymore—there is no ‘chain of command,’ and the law is far too slow to have anything to say most of the time. Inevitably, engineers have to learn to incorporate social costs and benefits into the decision-making process.

[…]

I often hear a willful disdain for moral issues. Anything that’s technically feasible is seen as fair game and those who raise objections are seen as incompetent outsiders trying to rain on the parade of techno-utopia.

https://33bits.wordpress.com/2011/06/11/in-silicon-valley-great-power-but-no-responsibility/

2011

Damon Horowitz

We need a “moral operating system”

TED talk: https://www.ted.com/talks/damon_horowitz

2011